Niamh O’Malley, Lightbox, Grimm 54 White St, New York, 15 December 2023 - 17 February 2024

https://grimmgallery.com/exhibitions/270-niamh-o-malley-lightbox/

Niamh O’Malley and Ciarán Murphy, in Conversation

https://elephant.art/niamh-omalley-and-ciaran-murphy-in-conversation/ 5 Jan 2024

Chance and Chaos: A Q&A with Ciarán Murphy and Niamh O’Malley

The two Irish artists are set to present parallel exhibitions at the New York outpost of Grimm Gallery later this month.

By Alexandra Tremayne-Pengelly 12/11/23 6:58pm

https://observer.com/2023/12/interview-artist-ciaran-murphy-niamh-omalley/

L'Essenziale Studio Journal of Visual Arts and Design Vol.06 October 2023

Vardaxoglou, London, 2023

Accompanying exhibition brochure designed by Varv Varv with text by Chris Fite-Wassilak available here

Link to Press Received: Ireland at Venice, 2022

Aemi Online: Niamh O'Malley, Glasshouse with an introductory text by Chris Fite-Wassilak

https://aemi.ie/works/glasshouse/

In Conversation: Niamh O’Malley, Dr Sarah Hayden and Dr Daniel Cid

Niamh O’Malley: Placeholder, mother’s tankstation limited, Dublin

26 February - 18 April 2020, Review by Aidan Kelly Murphy

https://aidankellymurphy.com/2020/03/20/this-is-tomorrow-niamh-omalley-mothers-tankstation/

September 2019, The Irish Times

AUGUST 2019 - The Irish Times

Aidan Dunne

JULY 2019 - Visual Artists Newsheet

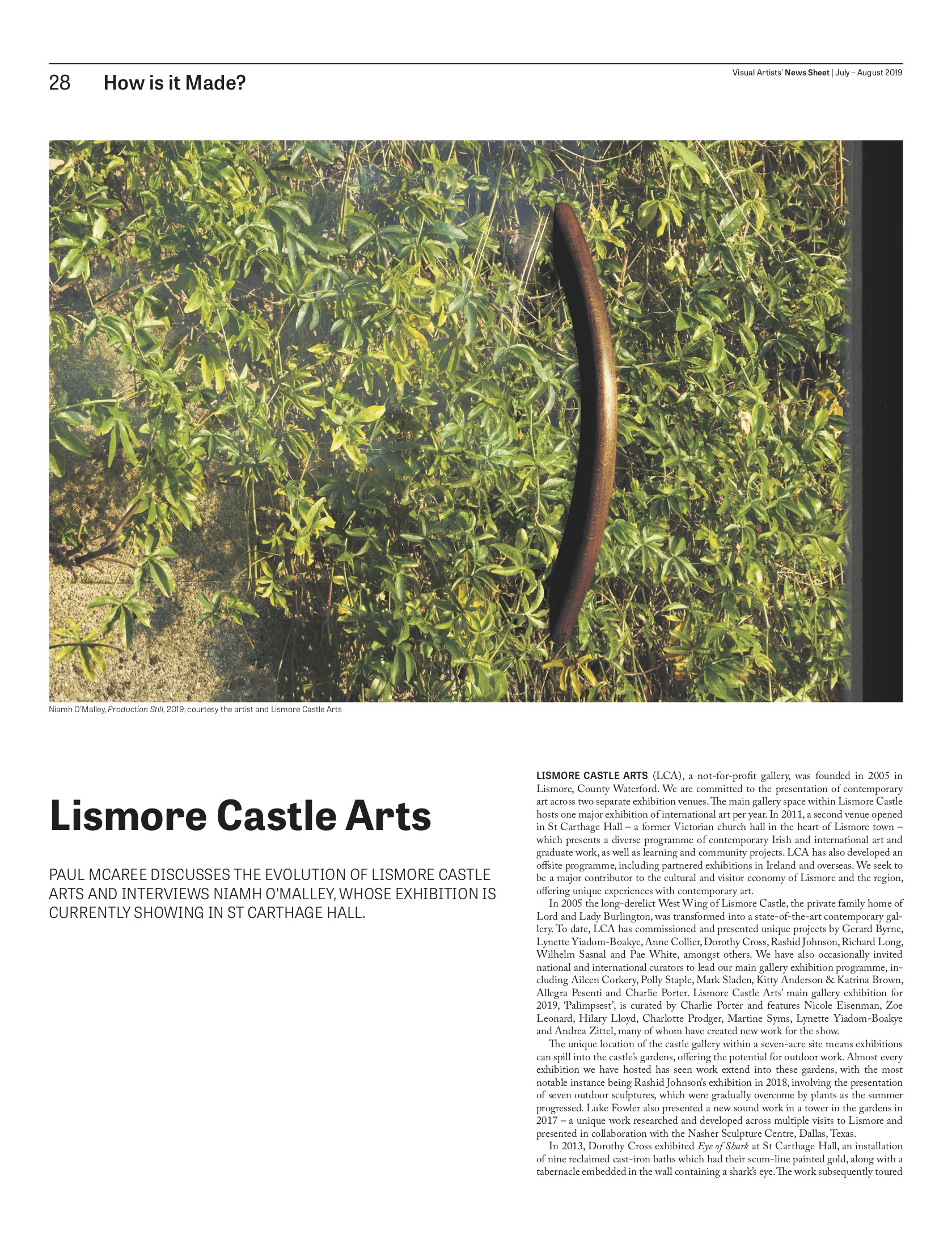

Paul McAree discusses the evolution of Lismore Castle

Arts and interviews Niamh O’Malley, whose exhibition is

currently showing in St Carthage Hall. https://visualartistsireland.com/lismore-castle-arts

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

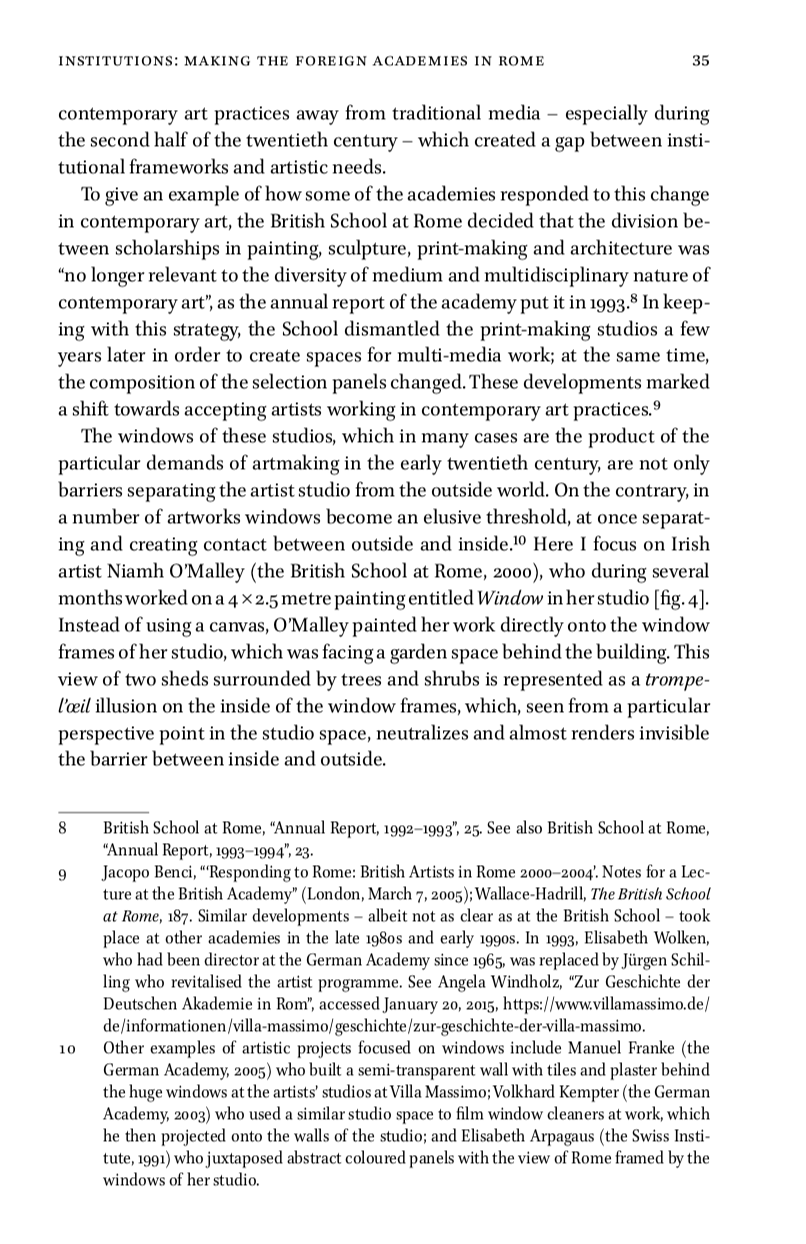

Artistic Reconfigurations of Rome: An Alternative Guide to the Eternal City, 1989-2014

Leiden/Boston: Brill Rodopi, 2019. ISBN: 9789004394216

In Artistic Reconfigurations of Rome Kaspar Thormod examines how visions of Rome manifest themselves in artworks produced by contemporary international artists who have stayed at the city’s foreign academies. Kasper writes about an artwork I produced at The British School at Rome in 1999/2000.

Augmented Geology, 09.06.17 - 08.07.17, KARST, Plymouth

The following text is part of the response by writer Lizzie Lloyd to the exhibition: Augmented Geology, 09.06.17 - 08.07.17, KARST, Plymouth

This section refers to the film 'Quarry'

0.4 This is the situation.

We are taken to a quarry, the site of simultaneous destruction and construction, to watch the compression of rock through the heat induced expansion of sand – glass. But the longer we look, rock’s apparently inert obduracy begins to morph under the pressure of our sustained attention. Like metamorphic rock, the quarry is pressed upon with insistence: sliding foliates of transparent, coloured and frosted glass glide across our field of vision. We don’t see it, we don’t realise it’s happening at first not until, until, with some delay, the distortions drag upon seams in the rock, warping them in ways we know cannot be true. Though modified, filtered, it is nevertheless true.

These low-tech intrusions of colour and surface undulations, see the world of solid rock ooze, slipping across our retina – liquefying foci and depths of field – returning them to their molten prehistoric states. Rock travels like bodies and language and looks; Robert Smithson knew this too.

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Journal of Contemporary Painting Volume 3, Numbers 1-2, 1 April 2017

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

‘Forms of Imagining’ Project Arts Centre, Dublin, ‘Garden’ (Online PDF) by Caoimhin Mac Giolla Leith

http://projectartscentre.ie/forms-imaging-publications-available-now/

LOOKING-GLASS

In his classic study of English Romanticism, The Mirror and the Lamp (1953), M. H. Abrams contrasts the pre- Romantic conception of art as primarily devoted to mimesis with that which displaced it, the idea of art as illumination.i Various works produced by Niamh O’Malley over the past decade, when considered together, call to mind this dichotomy between divergent aspirations for art - to reflect back to the viewer a world that is already familiar, or to cast light on one previously obscured – if only to reassert the limitations of both. Yet to suggest that she may be drawn to time-honoured debates should not blind us to the fact that she has re-engaged with them by means that have at times been highly original.

The first extensive body of work by O’Malley to attract significant critical attention, which she embarked upon in 2003, is a case in point. This was a series of what she refers to as ‘video-paintings’, a term that signaled early on a willingness to confound inherited categories and to dispense with any fidelity to the specificity of a given medium. Hyphenated terms such as ‘video-painting’ more often than not are intended to suggest a marriage of concerns and/or characteristics deemed somehow inherent to disparate mediums. O’Malley’s coinage, however, denotes a literal hybrid. In these works an image derived from video footage shot by the artist, but belonging more properly to a traditional genre of painting – landscape, streetscape, interior – is painted onto a canvas support, leaving certain details and sections of the picture blank. The looped original footage is then projected onto the partially painted canvas. The result is an uncannily shimmering ‘doubled’ picture in saturated colours, which becomes especially disconcerting, even ghostly, when the superimposed moving imagery is at variance with the static image beneath. At the end of the video loop the projected image suddenly dissolves, briefly but exquisitely exposing the nature of the artifice, before resuming and, by doing so, reanimating, without actually restoring, the work’s formative illusion.

Much that remains characteristic of O’Malley’s work, which has nevertheless evolved and diversified considerably in the intervening years, is already in evidence here. This includes her unique blend of the sensual with the schematic, as well as a kind of cat-and-mouse play between revelation and occlusion or, put more dramatically, between seduction and disenchantment. If part of what is at stake here is the desire to hold in productive tension the perennial imperatives of transcendence and criticality, O’Malley seems more than usually attracted to the mediation of such conventional oppositions. That disenchantment itself might, for example, harbour its own form of seductiveness is suggested by a revealing comment in which she professes her fondness for ‘stained glass [as] seen from the outside, all murky and flattened’.ii This observation also usefully draws attention to the centrality to her work of glass as a favoured material, in its multiple forms and functions i.e. as opaque, transparent or reflective; as something to be looked at, looked through, or both simultaneously, in effect. Regarding stained glass in particular she has the following to add to the remark already quoted:

'I read somewhere about how stained glass, as well as provoking interiority, is difficult to read, as our eyes are meant to make sense of light falling on objects rather than through them. So our ability to read the image is automatically secondary, [as] our eyes are preoccupied with the brightest spot.'

An extreme demonstration of this preoccupation with bright spots, as well as an intriguing anticipation of this latest exhibition at Project Arts Centre, is provided by Torch, 2007. This is a short, looped video, recorded at night, in which a meandering traversal of an urban garden is traced by torchlight, briefly illuminating disparate details of its flora. The work is projected onto a screen of stretched canvas painted black in a blacked out room such that the viewer is enveloped in almost total darkness, save for the shifting cone of projected light, which effectively mimics the original movements of the torch. Yet O’Malley seems no less interested in dark spots – or indeed blind spots – than in bright ones, as we can see from a pendant work, Scotoma, made the following year, in 2008. This is a five- minute video loop projected onto a rectangular panel of MDF on which a large, slightly off-centre stain has been painted in black oil paint, which corresponds to an obscured area of the projected imagery produced by placing a black piece of paper in front of the camera lens while filming. In this instance, a similarly wayward camera surveys the cluttered interior of an antique shop as well as the open vistas of a tree-filled public park. That the lingering examination of a small landscape painting supplies a notional portal between these alternating, visually compromised indoor and outdoor scenes suggests that, almost a century after Marcel Duchamp’s renunciation of ‘retinal art’, painting per se remains a privileged site in O’Malley’s eyes, a locus classicus for the exploration of what it might mean to look attentively and really see.

Her two-part exhibition at Project is in many ways a culmination of the concerns just limned. If Torch may be taken to epitomise one aspect of Abrams’ mirror/lamp pairing, the two-channel film installation Garden, 2013 epitomises the other, featuring as it does a pair of disembodied hands slowly panning and tilting a mirror, which occupies most of the frame.iii The moving mirror reflects shifting views of the garden in which the largely invisible mirror-bearer is standing against a wall of lush vegetation, yet without once catching sight of the entirely invisible camera-operator. This garden is evidently quite narrow as the level of detail in the mirrored image of the creeper- clad wall behind the camera is not inconsistent with that of the wall in front of it. The visual effect is to constrict the perceived depth of field to such a degree that the space occupied by the wielders of mirror and camera alike, and by implication the viewer herself, seems in danger of vanishing altogether. In spite of its lapidary quality and beguiling pictorialism, Garden thus calls to mind one notable aspect of early video art, from which it differs in most other respects. Rosalind Krauss argued many years ago that a crucial characteristic of early video is a collapsing of time and an attenuation of space, which she subsumed under the rubric of ‘autoreflection’ or ‘mirror reflection’, though she did not intend the latter term to refer literally to the deployment and/or representation of mirrored surfaces. Rather she likened the ‘vanquishing of separateness’ she discerned in certain works by Vito Acconci, Bruce Nauman and Lynda Benglis to ‘facing mirrors on opposite walls [that] squeeze out the real space between them’.iv

Krauss was at pains to distinguish the auto-reflection characteristic of early video, its constitutive ‘narcissism’, which she found problematic, from the self-reflexiveness of modernist painting, which she found commendable. Of course the definitive account of this self-reflexiveness is that provided by Krauss’s early mentor, Clement Greenberg, who described the evolution of modernist painting in terms of progressive stages of refinement, which is to say the gradual filtering out of all those properties painting had accrued through the ages that were not inherent to it as a medium. While this may seem to take us some distance from the work of Niamh O’Malley, which appears to play hard and fast with medium-specificity, the question of filtering, and the issue of the filter, in both mechanical and metaphoric terms, merits further examination.

A filter is a device designed to remove unwanted material. Its purpose is refinement, purification, and the general enhancement of a given experience. Most filters function discretely, drawing little attention to themselves or their mediating properties. This is not, however, always the case. Many photographers and film-makers, for instance, use colour filters in order to produce specific - generally defamiliarising, sometimes spectacular - optical effects. A pertinent example here might be James Welling’s 2006-9 photographs and film of Philip Johnson’s iconic Glass House. While O’Malley is sparing in her use of such effects - the colour film Quarry, 2011, is exceptional in this regard (as well as superficially comparable to the Welling works just cited) - the idea of a filter as a mechanism with the potential to distort as well as to enhance is suggestive, all the same. First, with regard to enhancement and refinement, a generalized conception of ‘filtering’ accounts for certain key decisions made in the production of O’Malley’s video-works. She notes, for example, that her decision to film Garden, in particular, in black-and-white ensured that the viewer is not unduly distracted by horticultural specifics, by the appreciation of individual plants and flowers, not to mention any symbolic associations this might entail (e.g. the intimations of romance or longevity prompted by a profusion of lavender wisteria). Silence is another mechanism deployed in her films, none of which have a soundtrack, in order to eliminate undue interference with the act of concentrated looking on the viewer’s part.

With regard to distortion, on the other hand, aside from the use of tinted and unevenly surfaced glass filters in Quarry, the most consistent use in O’Malley’s films of what might, at a stretch, be called a ‘filter’ is less a matter of distortion than an actual disruption of the flow of images. This is effected by the intermittent passing or placing of an opaque surface in front of the camera lens causing the screen to go black for a while. It is tempting to relate this alternating revelation and occlusion of the image – which has been such a notably recurring trope in O’Malley’s work from the outset, as we have seen - to Freud’s famous analysis in ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ of his infant grandson’s game of ‘Fort/Da’, which involved repeatedly discarding his toys and then retrieving them, as the compulsive repetition of a distressing experience, namely the disappearance of the mother. Freud interprets this game in terms of ‘the child’s great cultural achievement’, which is ‘the renunciation of instinctual satisfaction’ in allowing his mother ‘to go away without protesting.’v

This particular invocation of Freud would of course be difficult to justify were it not for the peekaboo character of so many of O’Malley’s works. It also, however, begs the question as to who - or indeed what - might constitute the dearly departed mother, i.e. the reluctantly outgrown source of previous pleasure, in O’Malley’s case. Might it simply be the art-historical matrix from which her work has sprung? More specifically, if somewhat surprisingly, might it be the medium of painting to which the work so frequently and so pointedly alludes? On the face of it this seems improbable, given the more obvious claims on O’Malley’s attention of the various mediums with which – unlike painting per se - she actually continues to work. i.e. video, sculpture, drawing. Even photography initially seems like a more suitable candidate, in spite of her limited recourse to the medium, given that one quality that binds Garden to previous film installations such as Bridge, 2009, Island, 2011, and Quarry is their shared indebtedness to the pictorial values of modernist black-and-white photography, most markedly in the solicitation of a protracted scrutiny of the tones and textures of stone, wood, wave and leaf. That said, according to a common account of modernist photography, its evolution is in fact inextricable from that of modernist painting, in that it increasingly devoted itself to the precise transcription of reality, which abstract painting was in the process of abandoning.

So it may well be that, ultimately, the history of painting - including the repeated reports of its imminent or actual demise over the course of her own life – has had a more profound and generative significance for O’Malley than that of any other medium. Stray pieces of evidence for such an unlikely assertion abound in her work, from theearly ‘video-paintings’, through the tachisme aveugle of Scotoma, 2008, to the studiedly anachronistic scenario of the academic life-drawing class in Model, 2011, and it would not be difficult to find in other key works such as Flag, 2008, and Bridge formal echoes of certain canonical modernist paintings. Further support for this admittedly tendentious reading of O’Malley’s oeuvre may be provided by the second element in the Project exhibition, which perfectly complements Garden. Set into a wooden seating platform is a large pane of glass, both sides of which bear painted marks here and there, ranging from fugitive figuration to unremitting abstraction. It might be argued in conclusion that this work deftly telescopes an entire history of Western painting from Renaissance theorist Battista Alberti’s pioneering account of the medium as a ‘window on the world’, through the rich and varied history of landscape painting, through early Modernism’s great challenge to painting in the form of Duchamp’s ‘Large Glass’, down to the self-consciously desultory mark-making of endgame abstraction in the face of recurring portents of the death of the medium.

Caoimhín Mac Giolla Léith, August 2013.

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Review: Frieze, ISSUE 177, MARCH 2016 Niamh O'Malley, Bluecoat, Liverpool by Brian Dillon

Niamh O’Malley

the Bluecoat, Liverpool, UK

For much of the past century, psychologists and the general public alike believed that humans dreamed solely in black and white. This spurious notion, it is now conjectured, was an artefact of exposure to black and white film and photography – though how exactly the self-deception worked remains unclear. No matter: the slumberous inner eye is washed by colour, just like the waking orb. Imagine, however, if colour drained away as soon as you closed your eyes, before dreams arrived. The lidded scene might resemble Niamh O’Malley’s small, dark pencil works and monoprints: hypnagogic grisailles troubled by migrainous flashes and voids. At their densest, these generally untitled fields of grey recall the inkblot drawings of Victor Hugo or Alfred Stieglitz’s ‘Equivalents’ series of cloud photographs (1925–34). If you saw them in isolation, you might think the Irish artist was artist committed only to brooding, hermetic opacity.

In fact, as her solo exhibition at the Bluecoat proves, O’Malley’s work has as much to do with clarity and transparency as sooty obscurity. Several works in the show are effected in glass that has been variously broken, scratched, painted on or leaded together and draped in fragments. Shelf (Curve) (2015) is a small, wall-mounted assemblage of dark beechwood and glass, the latter’s overlapping planes scored and smudged. In its modest way the work projects a kind of spectral modernism, the sort of thing the Irish designer and architect Eileen Gray might have confected during her long Parisian retirement. But the suspicion already – as with Tilted Glass (2015), a delicate sculptural sandwich of steel, beech, a clear pane and yellow glass lozenges – is that O’Malley is far more exercised by the perceptual lures of her forms and materials than she is by their possible echoes and referents.

One proof is in the two-channel video work Glasshouse (2014), which gives the exhibition its title. During a residency in Denmark, O’Malley happened on rows of old greenhouses, which allowed her to execute long tracking shots, left to right, past stained and broken windows, decayed mullions and open views of the dry salvage of late summer: brittle grasses, overgrown weeds, trees wilted past their prime. All of this in silence, and lustrous black and white. It turns out that O’Malley has in places cut the glass into clean curves, or inserted a second pane into the frame to further obscure the landscape on the other side; at times the windows are blanked out completely, like the whitewashed glazing of a disused shopfront. And, at such moments, the plants outside throw shadows on the glass, sometimes clear and sometimes hazy; as often in O’Malley’s work, precise details threaten to become obscuring veils through which another scene is almost visible.

O’Malley’s earlier work often involved projecting video imagery onto paintings, or partial paintings, of the same scene. Portions of the composition remained vivid and in place while others wavered or moved or vanished entirely. At the Bluecoat, there is a minimal reminder of this alignment of painting and moving image in Nephin (2014). In this half-hour video, the west-of-Ireland mountain of the title is circumnavigated by car while O’Malley tries to keep a small black dot or smear, painted onto glass in front of her camera, fixed somewhere near its summit. Inevitably she fails: farmyards, trees and hedgerows get in the way. But even when mountain and mark are both in plain sight and adequately aligned, the work seems to court a kind of blindness – concentration pursued to the limit may hardly be distinguished from distraction.

The painterly name for a spot, stain or blemish is ‘tache’: taken from the French, as in tachisme. But the word also means a catch, loop or button: something meant to connect or hold in place. O’Malley’s marks, whether on paper, glass or screen, are similarly ambiguous; they fix and obscure in the same moment, they draw attention to attention and thus also to its undoing. Appended to Nephin are two pencil drawings that depict a mountain that is itself a kind of blot on the landscape, oddly orphaned in an otherwise flat plain. The first drawing shows the mountain top, the second a hollow in its side – stain after stain, blot upon blot. And both drawings are immured behind grey glass, as if the detail is about to be swallowed by the dark at exactly the moment O’Malley has caught it.

Brian Dillon

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

http://www.corridor8.co.uk/article/review-niamh-omalley-glasshouse-bluecoat-liverpool/

23.11.2015 — Review Niamh O’Malley: Glasshouse Bluecoat, Liverpool, by Jack Welsh

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Review: ArtReview, March, 2015 by Chris Fite-Wassilak

Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov’s ‘kino-eye’ was a film montage method that could, as he saw it, show things in a way no human eye could see, and would elevate human consciousness. On the whole, film’s effect on humanity has largely gone the other way to Vertov’s prediction. But Niamh O’Malley has, for the past few years, produced a series of black-and-white videos that calmly survey a landscape, yet also slowly let what we’re seeing merge with how we’re seeing it – shadows conflate with the screen, blinking becomes linked with editing, the eye becomes the lens. We’ve already become, O’Malley seems to suggest, Vertov’s living kino-eye, editing and shaping things with every glance; we just habitually ignore the fact.

This latest exhibition is no different, with the video Nephin (2014) as its centrepiece, documenting a passenger-side view of a car journey circling a low, grass-covered mountain. The rounded landform stays centre-screen as we pass by houses and fields, with hedgerows occasionally blocking the view, but after a while, it’s likely that the only thing we’ll focus on is a small, black dot that persists on the upper right of the screen. Whether a speck on the car window or the camera lens, it’s a small but effective reminder of the limits to how we view the world. As a further reminder, two tall, framed panels of coloured glass, one pink and one yellow, flank the video screen, letting us view the scene in another hue.

It’s a point that this reserved and refined installation of 17 works of drawing, glass sculptures and two films continually reemphasises: that seeing is always layered, always filtered, always framed. Several drawings depict the same mountain, rock or mound of dirt, each presented behind a speckled pane of tinted glass. But it’s when O’Malley all but gives up on her chosen subject of landscape that her bio-structuralist meditations become more productive. The small Untitled (2014) is a dense weave of short, modest pencil marks, accumulating and almost merging with the lines and shadows projected by the pocked layer of glass that covers it. The real heart of the show feels tucked into a few hidden corners of the angular concrete gallery: Shelf (2014) is a small stretch of beech with three pieces of glass propped on top. Here, a roughly L-shaped shard of yellow glass is mirrored by a grey fragment that resembles it, though its dark brother is lined unevenly with copper. Both of them form a miniature stage for a rectangle of clear glass, smudged with a blotch of white paint; here, O’Malley distils her entire show in one small breath.

The two-screen video Glasshouse (2014) is ostensibly a slow pan across the broken and dirtied panes of a greenhouse, at first seeming like a widescreen panorama, our minds naturally connecting the two screens as the scene passes from right to left. It’s only after a concentrated few minutes that you can distinguish the stereoscopic effect and realise that the two screens aren’t linked, in some cases even showing the same stretch of the greenhouse. It’s in the small gap between the two monitors that the work takes hold, the darkness that allows our mind to invest in, and effectively create, a new unified image; and it’s in this gutter that O’Malley excels.

This article was first published in the March 2015 issue.

http://artreview.com/reviews/march_2015_review_niamh_omalley/

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Interview with Maeve Connolly:

thisistomorrow http://thisistomorrow.info/articles/interview-niamh-omalley

The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, 12 December 2014 – 25 February 2015

Niamh O’Malley’s current exhibition at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, affirms her ongoing interest in the processes through which images are constructed, revealed and obscured, and her continued capacity to estrange apparently familiar objects and environments. But this gathering of entirely new works, including video, sculptural assemblages, constructions and drawings, also seems to mark a subtle shift in her practice. As recently as ‘Garden’, her 2013 solo show at Project Arts Centre, O’Malley was focusing her attention primarily on practices of viewing, and associated mechanisms of illusion and projection. In The Douglas Hyde Gallery, however, the formerly central position of the viewer has been displaced, or perhaps supplemented by an exploration of relationships between things and images.

‘Nephin’ (2014), is one of two new HD video works produced specifically for this show. Taking its title from a mountain in northwest Ireland, this work seems initially to provide a point of orientation for those familiar with your earlier video works. I’m thinking here particularly of ‘Flag’ 2008, which tracked a precise and silent circular motion around its billowing central object. ‘Nephin’, however, suggests a much more dramatic sense of pursuit, because the mountain is framed as a kind of target that seems to constantly escape the camera. Is it useful to read this work as a pursuit, rather than a study, of the mountain?

‘Nephin’ is a 21min 31sec silent video loop in black and white. It was filmed from a car through a pane of glass which had a small black mark painted on it. It presents the circumnavigation of a mountain in the west of Ireland. I was certainly interested in the sense that that image of the mountain is constantly eluded; the path of the road sometimes twists the eye/camera away from the landscape, bumps in the road unsettle the image, the hedges occlude and reveal, and the mountain itself shape-shifts as you travel. There is no point in the video where the camera settles upon a framing. The black mark on the glass is fixed in relation to the lens and becomes, in my understanding, some sort of extension of the eye or even the pointed finger. A marker of attention, trying to settle on its object, it steadies the chaotic foreground; it is a constant reminder of the intention, to see the mountain. Many of my previous videos have used the fixed camera/framing as a useful space of containment within which to ‘study’ the site or subject which has often been quite unfamiliar to me. In ‘Nephin’ I am faced with the idea of producing some sort of document of a mountain, a landmark, the ultimate still image or fixed point in that it stands in a different time-space to ours. I think I know it very well and therefore risk unknowing it through scrutiny, this may have led to the resulting relentless pursuit within the work.

In ‘Nephin’ there seems to be a deliberate confrontation between thing and image, as though the mountain resists its reduction to image. Would you see this relationship between thing and image as important in the show overall, or in the relationships between its component elements?

Nephin, as a dominant feature on the Co Mayo landscape, is often pictured or ‘imaged’, and the space of such ‘images’, as copies of a copy (our select and often flattened reading) is a powerful one. It seems to me that to produce an image is to extend the nature of the original ‘thing’ into one of subjectivity, which can perhaps be enough … or all we can manage. In other words, of course it is never the ‘thing’ but to circle or circumnavigate that problem reminds us it exists.

Perhaps because my own research is currently focused on transport, both imaginative and actual, I was struck not just by the forms of motion in ‘Nephin’ but also by your interest in Zizek’s concepts of ‘discord’, which he explains through reference to the ‘disproportion’ between the inside and outside of a car. Zizek notes that while cars look and feel small at first, they become more spacious when ‘outside reality’ is viewed through the barrier of the car windows. Would you see these ideas as relevant to your extensive use of glass in the show, in sculptural assemblages, framed works and also in the two-channel HD video ‘Glasshouse’ (2014)?

‘Glasshouse’ is a silent 2-channel video in black and white, filmed near Odense in Denmark. A fortuitous site with rows of derelict greenhouses afforded the possibility of a lengthy tracking shot where the glass panes could be recomposed and positioned in a painterly timeline. I’ve long been interested in surfaces that function as boundaries or barriers between one thing and another and the arrangement of different opacities within the video at times positions the background landscape as simply another surface to be panned and scanned. The ability of glass to become a screen, which distances or somehow re-surfaces the real, on which we can view or imagine the world (like the car-windscreen) is fascinating. In some moments of pure clarity, however, such as the moments in ‘Glasshouse’ where the glass is completely removed, the idea of the open window is reconfigured as a potent intrusion of noise-like reality. In other works in the exhibition such as ‘Double glass, floor’ and ‘Glass’ (both 2014), I am trying to examine some of the supposed limitations and the actual flexibility of the medium. Glass with its implicit translucence and fragility also embodies a state of solidity. It is an object with depth, colour and surface. It can be looked at or looked through. In these instances I’ve painted on both sides of the panes of glass. I’ve held glass horizontally just off the floor and leaned it against the gallery wall. The painted marks are indexical, one mark leading to another, a composition in time. The marks sit unabsorbed on the glass – and lie also as marks on whatever the glass itself reveals through its transparency or its reflective surface. The lack of absorption in the painted glass works is contrasted in the works on paper where I think of the imprint, the marks made that cannot be erased, the surfaces that retain mark and memory, compressed and sometimes held under glass in a frame. The mono-prints for example are like photographic stills; the ink sits into the surface and slowly develops and forms a skin.

There are two transparent, screen-like objects in the show, ‘Stand (Pale straw)’ and ‘Stand (Rose)’ (both 2014), that seem to invite repositioning or use in relation to other elements of the exhibition – could you expand on their propositional quality?

The Douglas Hyde exhibition has been a new kind of exercise for me in expanding on the relationship between my still works (drawings, paintings, prints, sculptures) and the moving image pieces. Works like the two ‘stands’ hope to animate the viewer and in doing so reframe or filter the gallery space, for the visitor and artworks alike. Some of the works in this show are ‘images’ not trying to be things. Others are devices, sometimes lifted from experiments in front of the camera back into a space where they can become ‘things’ turning other things into ‘images’.

The exhibition includes a wall-mounted sculptural work, ‘Canopy’, which again suggests functionality. But would it be fair to say that here the proposition is more directly addressed toward the architecture of the gallery?

Perhaps, in that it was wonderful to work within an architecture that allowed me to extend the exhibition vertically and this particular space, which I know and love, could not help but influence this new body of work. The grey glass of ‘Canopy’ can hardly cast light, situated as it is against the concrete ceiling, but it reminds you of the ceiling. It does not need to provide shelter but for me it does also conjure the distinctive view from above and descent into the bunker-like space that exists within The Douglas Hyde Gallery.

Perhaps because its scale and placement frustrates its use as an actual shelter, I wonder if ‘Canopy’ also draws attention to the considered absence of sound in the exhibition, and perhaps more generally in your work?

I find a paring back is necessary, perhaps even a constituent part of any art-production. Sound is only one thing that is eliminated. Perhaps it is more often commented on because we read video in relation to cinema. I think I understand video as another extension of the image-making I work with in painting and drawing, so sound is just another missing part (like what lies outside the frame) in the particular form of attention that is presented. Sound also plays out time in a very particular way. I like the time-space of the works to be ambiguous, to strip duration of agency. Which lasts longer; a sculpture, a video or a drawing?

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Exhibition Review: Enclave review by Rory Prout

https://enclavereview.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/prout-niamh-omalley.pdf

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************Exhibition Review: Paper Visual Art by Nathan O’Donnell

http://papervisualart.com/?p=11055

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Essay by Rebecca O'Dwyer from Publication: A Rethinking of Place (2014): Niamh O’ Malley, Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin

https://rebeccaodwyer.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/pdf-final.pdf

A Rethinking of Place

I will begin with a reverie of sorts. Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 film Wild Strawberries tells the

story of the Swedish professor Isak Borg, a ruthless and misanthropic man now in his seventy-ninth year. While travelling to receive an academic honour – the pinnacle of his hitherto illustrious career – Borg slips in and out of a series of enigmatic daydreams. He has, as one of his dream’s protagonists states, been ‘accused of guilt’: this guilt finds form in a series of delirious reminiscences of a past he deemed all but irrelevanti. Borg’s journey is two-fold: literal, but also - more specifically - towards the shifting site of memory itself. In so doing, it affirms the hallucinatory character both of memory and cinema itselfii. The familiar pastoral backdrop, captured in the sultry heat of a high northern summer, is rendered strange to Borg, remediated by the disquieting discrepancy of past to present. His memories become distorted and troubling: the countryside too becomes subject to this same process, growing almost threatening in the wake of a rethought past. For Bergman, the place of memory does not sit still: neither terra firma nor solace, but instead a cluster of signifiers being endlessly rethought and remade anew. As William Faulkner once famously wrote: ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past’iii.

There is something of this sensibility within Niamh O’ Malley’s work. In particular, the film Glasshouse (2014) shares with Bergman’s aesthetic a kind of intense dryness: in it, all moisture appears sucked from the frame, the scene’s stillness like that sensation when, just before fainting, the senses become somehow sharpened and attuned. Only here, now, there remains no colour or sound. All that persists is a kind of drought, baited breath: the dizziness of attention. Glasshouse calls to mind a hot airless summer’s day, almost hallucinatory: the scene, captured in lush cinematic tones, does not appear as though simply in black in white: rather, the colour seems purged from the frame, pushed out of it as though by osmosis, bringing with it the air, and the sound. All that is left is the studied process of looking as the camera moves seamlessly from left to right along the glass panes, a rural scene idyll disappearing here and there as the glass veers towards opacity.

Though Glasshouse is a slippery work: it obscures and retreats from view, creating an impasse between us, and the intimate garden vista it purposefully disrupts. A site of artificiality, the glasshouse creates the conditions for something not typically possible: similarly, O’ Malley’s

work creates the conditions for a different kind of looking, by disruption. Here the glass panes have been tampered with, withdrawn and reinserted to control the tonality – and thus our grasp – of the scene. The camera, focusing and capturing, doubles this logic. Glasshouse instead presents a semblance of looking; a looking that folds the act of making back in towards its process. O’ Malley’s work, in circumnavigating the process of just looking – if that even exists – is actively wanting: it works to remake as it sharpens its gaze.

Both Glasshouse and the accompanying film work Nephin (2014) adhere to the artist’s fascination with place: this has been commented on before, of course. These two works, however, circumnavigate its typical representation. In them, the scene is directly wrought in an attempt to reconfigure the viewer’s relationship to it: panes of glass, moved and manipulated so as to deny the scene’s easy consumption (Glasshouse); a small, tremulous black mark atop a pane of glass before the screen, its shudders echoing the camera’s jolting trail around the foot of the mountain (Nephin). There is a sense that O’ Malley shirks from a forthright depiction of landscape, instead choosing to imbue the image with a more honest kind of interruption – made real and physical – rendering it both jarring and quietly demanding. Both Glasshouse and Nephin approach their places obliquely, tenderly denying the possibility of their full comprehension, and instead choosing to make as they look. O’ Malley, I learned, grew up in the shadow of Nephin. The second highest mountain in Connaught, at some 2,646 feet, it would certainly make a striking, if somewhat foreboding, tableau. And yet the places closest to us generally slip towards invisibility, though we might certainly accede to their aesthetic beauty, in the event of some gentle reminder. Still beautiful, but becoming well worn, these places slip off the tongue. To engage it truthfully, Nephin needs to be re-formed and imparted with a degree of strangeness.

To go back to Nephin as O’ Malley does here is not to be taken lightly, but as demonstrative of a rethinking of that place, an engagement, never passive, that seeks to unravel it as it creates. This unravelling of place is a constant motif of O’ Malley’s. Often, it appears as though she works by a process of extraction: particularly in her films, this involves an elimination of each extraneous element; sounds being the first to go; then, gradually, the colour. Nothing is allowed to get in the way of attending to this site at hand. And yet a pure objective looking is unimaginable: a multiplicity of screens and barriers surface, mnemonic or otherwise, blocking access to the thing itself. So too with the barriers, screens and gestures of layering that populate her sculptural works: at each point, the act of looking is broken up and

interrupted, attention thus brought to the intrinsically subjective and bodily process of looking: messy and often incoherent, but perhaps more faithful to the task of representation.

One sculptural work, Glass (2013), consists of a large pane of double-sided glass, leaning at a slight angle away from the ground, and held vertical by lengths of steel. Standing at more than human-height, the viewer is free to fully circumnavigate its form. Painted atop one surface – part translucent, part reflective - are irregular black marks that disrupt our full comprehension of the scene. Every view, our bodies notwithstanding, is already marked by a trace: in such a way, Glass permits not one pure view back onto the world. Each view, like each act, bears the mark of something – seemingly external - to the frame. For O’ Malley, then, the act of making shares the same problem as that of looking: each desires an impossibly unencumbered viewpoint, from which it might look or make wholly anew. In Nephin, this impossibility is made manifest through a visual shorthand that condenses a constellation of subjectivity to a single, slight mark. The minor, the subjective, asserts itself, negating the impulse towards easy and thus unthinking consumption. A kind of positive and productive digression, O’ Malley’s object thus reconfigured contains the seeds of a more authentic form of engagement: be that with place, with memory, or with the responsibility of their subsequent representation.

Rebecca O’ Dwyer November 2014

i Ingmar Bergman Wild Strawberries (1957)

ii Recently I read Clio Barnard, the director of The Arbor (2010) and The Self Giant (2013), describe

cinema as a ‘collective hallucination’.

iii William Faulkner Requiem for a Nun (1951) New York: Random House, pg. 92

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Niamh O'Malley: ‘The Mayo Collaborative’, 2013- ArtForum, December, 2013 by Declan Long

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Through a Glass Darkly: Some Recent Work of

Niamh O’Malley by Luke Gibbons

‘Niamh O’Malley’ (monograph) published Linenhall Arts Centre, Ireland, 2013

Our perception being a part of things, things participate in the nature of our perception.

- Henri Bergson1

Writing of the problems presented by the Irish countryside to art, Ernie O’Malley noted that while painters were often aloof, it was the landscape itself that moved. Hence the array of effects ‘which may merge slowly or change rapidly . . . cloud forms rapid in movement change land values as they pass overhead.’ It is for this reason, O’Malley writes, that there is a distinctive ‘relation of the impersonal to the personal’, as if the object of vision were a subject in its own right.2 Though he does not mention it, the still image is also compromised in these circumstances, as nature itself bears witness to a passing of time that calls for the moving image, rather than the single take of a moment. It is these concerns that inform Niamh O’Malley’s vision, as the closer we get to reality in her work, the more perception intrudes on the scene. Human beings seldom appear in the frame but there is little doubt about the presence of a spectator, or a visual medium. In one of her few works to feature the body, ‘Model’ (2011), a male model shifts position on a dais to assume the pose of a classic Greek statue. At times, the image comes across as a still photograph, but the blowing of a tree in the wind, visible through a window behind the model, destroys the illusion. At certain moments, the tree is at rest and stasis is all but confirmed until, in a corner of a windowpane, a cloud almost imperceptibly shifts position. Time and space are subject to change even though, as Walter Benjamin wrote of the pressures on the image under modernity, dialectics may be at a standstill.3 In one of his last works, the French philosopher Merleau-Ponty wrote of the invisible that constantly haunts the visible, not in the sense of something unnoticed, or an object hidden from view, but in the conditions of seeing itself, what is brought to the field of vision.4 Niamh O’Malley relentlessly returns to this primal scene, the mote that lies in the eye of the beholder. In Screen (2011), a Mondrian-like minimalist structure of wood, glass and paint on the gallery floor purports to give an uninterrupted line of vision, until we realize at certain points that we are looking at a reflection of its surroundings – a reflection that also provides amputated glimpses of the viewer. There is a large black circle on a central plane of darkened glass, reminding us of the blind spot that cuts across vision, and in Scotoma (2008), this is the subject of a continuous loop film, as if the eye – or camera – is casting itsown shadow, condemned to view the world through a glass darkly.

In ‘Island’ (2010), different shades are encountered, the ghostly rituals of pilgrims who have visited St Patrick’s Purgatory at Lough Derg for hundreds of years. A voice in Seamus Heaney’s ‘Station Island’ poetry sequence warns the poet against treating ritual as simply ‘going through these motions’, but it is precisely the ritual of motion itself, as in camera movements, that is at stake in O’Malley’s ‘Island’.5 A series of slow tracking shots movingfrom left to right mark the approach to the island in close-up, but are interrupted by a black fade entering from the right. This could be a cinematic device or a visual effect – but it could also be an actual obstacle occluding sight, and it is this uncertainty between inner and outer worlds that haunts these images. The tracking shots move onto the island, enacting point of view shots of paving stones where thousands have walked or kneeled, but as the camera continues its passage, it faces limits; the shore edge, or an embankment. Whether it surmounts these (as a spectral presence might do) is left open as edits, in the form of wipes, cut to a new scene: again, it is unclear whether inner or outer worlds are calling the shots. There is no sign of people but over a long ditch or wall, crosses are visible, followed by silhouettes of a tree and church in the distance, framed against an overcast sky. In a circular motion, the camera then returns to the choppy waves encountered at the outset as if, for the renewal of the faithful, the only constant was water.

If an island is surrounded by water, a bridge crosses it, but in ‘Bridge’ (2009), the substantive silhouettes of the bridge appear asabstract forms, imposed as diagonals, or like sections of Malevich’s Black Square, on the screen. A ‘frame-within-a-frame’, like a viewfinder, moves hesitatingly across the pictorial field in search of focus but is out of focus itself, unable to contain what is around it. The bridge acts as a frame of sorts, its scaffolding connecting water and sky as well as one bank of the Humber Estuary with the other.

In ‘Flag’ (2008), the camera tracks an unmarked flag in the centre of the image but the windswept agitation of the flag, and its change of shape as the camera moves in an arc-like movement around it, throwing the eyes off-course. The screen itself is filled out with distracting details of brightly lit office windows, neon signs, and so on, in the background, while the diaphanous fabricof the flag also acts as a small screen within a screen, with lights barely visible through the fabric. The camera turns full circle, only to begin its journey again in the continuous cycle.

For Merleau-Ponty, the invisible that lies at the heart of the visible is due to the fact that the eye does not only see: it is also seen. Even objects return our gaze in this scheme of things, as if the world is also aware of being looked it. Kneeling stones placed for pilgrims in ‘Island’ tell their own silent story, but in ‘Quarry’, stones are remnants of deep historical time, showing the cracks and fissures of centuries. Beginning with a blurred image of boulders piled below an imperturbable rock-face, a slow wipe from right to left across the screen literally appears to wipe the slate clean. Stones take shape as if cubist forms are composing themselves in the breaker’s yard, evincing the sense of time and movement introduced into the image by Cezanne. Still life itself seems animated: in a green tinted image of a block on the ground, stone itself appears to emit the pulsations of breathing until it transpires that a ripple dissolve, of the kind that introduced flashbacks in film, has been pulled across the screen. The ripple dissolve simulates the crimped effect of water but in a succeeding image, liquid appears to strafe the surface of rock, giving the impression of rain. No sooner do we conclude that a colour tint has been added to black and white images, moreover, than yellow marks, probably breaker’s inscriptions, unsettle the monochrome surface, at once inside and outside the camera.

Time is also somewhat out of joint, at least with the still image. Presented with a smooth wall surface, it is not clear whether we are encountering a photograph or a motion picture, until – the stirring still also noted in ‘Model’ - a faint disturbance of vegetation in the background reveals movement. In the work of the Belgian artist David Claerbout, photographs come alive, the still image of a Dutch landscape betraying disconcerting signs of rustling leaves on a tree.6 As Thomas Levin notes, this violates one of the fundamental tenets of ‘indexical’ images, the ‘homogeneity of their signifying surface’.7 In Claerbout’s case, the disruption is introduced by subtle digital effects, which throw into question the referential claims of the rest of the image. In O’Malley’s ‘Quarry’, however, a similar impression is produced in real time as if a still image and motion picture fuse in the same shot. In case we attribute motion to special effects, a later image shows the finished surface of a wall in which one of the stones almost imperceptibly begins to move, easing itself of its niche in slow motion until it finally tumbles out. A second stone is dislodged in the process by the ensuing cavity but there is no sign of human intervention, in the actual scene or from post-production effects, only a tight cropping of the visual field. It is as if erosion is taking place before our eyes, and invisible geological time unfolds on the screen.

Niamh O’Malley seems intent on retrieving the referential claims of the camera on both space and time in an age of digital production, but by being no less true to the potential the medium as well as the object of vision. Under digital production, the ‘real’may be usurped by the virtual reality of the ‘simulacrum’ (in Jean Baudrillard’s terms) but the answer to this is not to posit an inert ‘objective’ reality, untouched by human presence. For O’Malley, ‘indexicality’ and real time hold their own not despite, but because of, the primacy of perception: it is displacement of perception itself that removes the personal from the impersonal, and severs contact with the landscape of our lives

NOTES

1 Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory [1911], trans. Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer. (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1911), 237.

2 Ernie O’Malley, ‘The State of Painting in Ireland’ [1946]; ‘Review of Thomas MacGreevy’s “Appreciation and Interpretation of Jack B. Yeats”’ [1946], in Broken Landscapes: Selected Letters of Ernie O’Malley 1924-1957, eds. Cormac O’Malley and Nicholas Allen (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 2011), 403, 397.

3 Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 10.

4 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible [1964], trans Alphonso Lingis (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1968).

5 Seamus Heaney, ‘Station Island’, in Station Island (London: Faber, 1984), 71.

6 Thomas Y. Levin, ‘You Never Know the Whole Story: Ute Friedrike Jurss and the Aesthetics of Heterochronic Image’, in Art and the Moving Image, ed., Tanya Leighton (London: Tate Publishing/Afterall, 2008). 463. Levin discusses Claerbout’s 1997 video installation, Ruurlo Bocurloscheweg 1910.

7 Levin is here referring to the fact that photography and film in the age of mechanical reproduction register physical traces of reality through the imprinting of light on film. It is this relationship that is jeopardized by digital production, notwithstanding a similar surface illusionism.

************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Niamh O’Malley by Matt Packer

‘Niamh O’Malley’ (monograph) published Linenhall Arts Centre, Ireland, 2013

At first, it's difficult to know if we're moving. When I refer to 'we', I'm actually referring to the camera. We are seated within a darkened projected room, so of course we're not moving. Or not yet anyway. Not for another 6 minutes or more. This is just the beginning.

In Niamh O’Malley’s video work Flag (2008), the camera slowly and tactically circles around a flagpole, set high above the night sky of the Helsinki docklands. The sparse street lamps and lonely illumination of office security lighting appear like a backdrop of distant stars. The pole remains centrally placed in the frame, effectively cutting the frame in two and acting as the organising axis of the camera’s circular line of movement. The flag itself kicks against the wind, and does what flags typically do, flitting this way and that, shifting its emphasis from the right to left-hand side of the frame as the camera completes its orbit and catches different directions of the breeze. The flag is made of semi-transparent fabric and carries no image or icon. Its only demonstration is one of its own material abilities, its texture, responsivity, and transparency. And all this toward a camera that seems to have the singular task of satisfying these same qualities. In Flag the camera performs the flag, and the flag performs the camera, to the full extent that the work (quite literally) draws a circle around traditional alignments of perception, subjecthood, and the camera as medium.

In O'Malley's work, the notion of a 'medium' extends beyond the material and technological specificities of artistic practice such as sculpture, drawing, or video. If we go looking for 'medium' through the back catalogue of her work, we quickly get deferred. Perhaps by her three dimensional sculptural work that often involves two-dimensional planes, screens, windows, or painting surfaces. Perhaps by her drawings that are often framed in coloured glass, thereby superposing the medium of graphite on paper with the extra mediating conditions of tinted glass. Or perhaps by her videos that counteract the form, structure, and transmission of her subjects, so that these subjects seem to take on the condition of being mediums in their own right. In O'Malley's work, mediums seem to be everywhere, inescapably and in layers: each proposing a slight but significant re-organisation of our perceptual compass.

This sense of layering is exemplified in Bridge (2009), a video work that presents a sequence of views of the Humber Bridge in North East England. Shot in black and white from the shoreline, aspects of the bridge's structure cut sharp lines and silhouettes against the cloudy sky. All sense of its monumental scale and workaday traffic loses dimension in its graphic reduction, further achieved by the lack of visible movement in the frame. Only in occasional scenes do we see a bird in flight, the gradual changes in the cloudscape, the ripple patterning of water.

There are other movements, but not similarly in the deep of representational space. These movements take place directly in front of the lens, as though part of the camera apparatus itself. Through the duration of Bridge, our views of the bridge become interposed with a succession of black masks or filters, that slowly cross the frame, move left and right, and obscure sections of the image. Some eclipse the image entirely and support the rhythm of scene changes. Other filters are transparent except for a small rectangular outline like the focus target in camera's viewfinder. The alternation of these filters play a part in the graphic assembly of the bridge, reinforcing the bridge's flat formal qualities, its symmetries and contours. The tensile wires of the bridge's construction and its vertical concrete supports, interacting with the black filters like cut out shapes on a page.

The graphic assembly that takes place in Bridge is also, in a sense, a disassembly by another description. Space becomes disassembled as images near and far (both upon and beyond the lens) find continuity with one another. The black of the bridge's silhouette; the black of the filters that pass across the frame; the black of the fabric projection screen in the presentation of this work; all of these blacks take on an equivalence so that the spaces between the bridge to the camera, and between the camera to its eventual projection, collapse into one and leave us metaphorically in the dark. Indeed, perception itself seems to become disassembled in the full effect of O’Malley’s work. Just as Rosalind Krauss described of Richard Serra’s film Railroad Turnbridge (1976), where the camera and the bridge in Serra’s film partake in a 'relationship, a transivity … traversed by the mutual implication of back and front, thus creating a visual figure for the pre-objective space of the body', O’Malley’s Bridge exercises a similar visual figure. The act of looking at a bridge is rarely made so physical.

In the characteristic give-and-take relationship that O'Malley develops with many of her subjects, it makes sense that she would be interested to produce a substantial work in a large limestone quarry in Kilkenny, Ireland. A quarry is, somewhat paradoxically, a negative imprint of its productive output, a space that is shaped and defined by the processes of removal, a structure in reverse. As a subject, a quarry comes ready loaded with some of interactive layers that we see elsewhere in O’Malley’s works. In the opening sequences of Quarry (2011), we are presented with details of rock that have been cut, scarred and fashioned by the processes of extraction. It’s possible to assume that these are a sequence of still photographic images. Only later in the video are there signs of movement: a tumbling rock; the water down a sheer rock face; the slow invisible force of a rock face being pulverised. There is nothing to see of the heavy technology that is at work here. As the video progresses, we yet again see filters. An out-of-focus image becomes in-focus. Colour casts become removed. In other instances, we detect the movement of filters that seem to carry no effect whatsoever. Whereas the interactions of filters in Bridge are tensioned between black and white, and between assembly and disassembly, the filters in Quarry operate on a different axis of abstraction. The filters here do not presuppose a ‘naked’ image, suffocating under all these effects. In an entropic loop that is someway analogous to the status of the quarry itself, the filters here only reveal the possibility of other filters. We acknowledge one only to encounter another. The work seems to declare that all images are mediated, the only difference being that some images are more apparently mediated than others.

It is remarkable how the body appears and re-appears in O'Malley's work, which at first impression is decisively absent of people and human activity. The movement of the filters that pass across the frame in Bridge, and that occur again (though significantly differently) in other video works such as Quarry and Island, are unmistakably movements of human hands. Although we rarely see the body at work behind the camera, we’re left with enough human inflection to introduce us to the tacit contract with its operator. This is a body that performs under the regime of technology and against its measure, doing its best at approximating an effect that is easily possible with editing software. Approximation, of course, is precisely the point. A reminder that we are not witness to a transparent process of depiction and representation, but one that is built with layers that are partly received by technology and partly counter-constructed by our own hands.

Perhaps, of all O'Malley's recent video works, the absenting of human signs and registers is most pronounced in Island (2010); a work produced at a historical site of religious pilgrimage in Lough Derg, County Donegal. In this work, the camera moves steadily though a concrete landscape that seems to carry the dreams of inhabitants that have long since vanished. All investments seem to have been exasperated. All life disappeared. The water lapping at the weather worn edges of the compound, only affirms what’s missing here. The camera in Island scans this place like a post-human rover, indiscriminate to the spiritual investments that have been bestowed here, and yet with a calculus of the rhythms and routines of the lives that have marked this place. This is a place of two halves after all, for 'connecting with suffering and starving people of our world, while keeping in touch with the soil and the rocks of the earth'; that, according to the website that still advertises retreats here. Like the flag in Flag or the bridge in Bridge, we might consider that the island in Island carries similar properties of a medium, shaping the conditions of its own image. The camera registering the visible discrepancies of material and spiritual agency, while the lack of sound (as in many of O’Malley’s videos) only emphasising the volume of missing pieces.

A shift of subject has taken place in more recent years, from the monumental spaces and significations of Quarry, Bridge, Island, and Flag, through to the more intimate and less travelled reckoning of Garden (2013), a work produced in the space of the artist's own home in Dublin. It was Robert Smithson in his ‘Cultural Confinement’ essay who once equated gardens with other mediums of picture-making, stating that 'gardens are pictorial in their origin – landscapes created with natural minerals rather than paint'. And for O’Malley, the garden is also a medium of conjuring images, a portal between intimate, domestic confines, and the space beyond. Garden exists as a double projection on two adjacent screens, each video presented onto a vertically orientated leaning frame. Throughout the two videos, we see mirrors being held askance, at angles to the camera. The mirrors defer our gaze toward other, reflected, aspects of the garden. Sometimes there are slivers of sky. Sometimes there is the detail of stonework at the garden’s perimeter. The mirrors tilt and move our gaze through this space, and though it is impossible to know just how large and expansive the garden is, the space seems constantly renewable in its perspectives.

There are numerous layers within Garden, and within each layer, a frame, a screen or a window. There is the frame of the garden itself, of course, with its organising limits. There is the frame of the camera that cuts all life in front of it into rectangles through the viewfinder. There is the frame of the projection screen, which, as always in O’Malley’s work, assumes a physicality and sculptural imposition of its own. Then there is the frame of the mirrors that feature in the sequences of this work, through which our viewing become both conditioned and extended. Finally, perhaps, we should acknowledge the frame of the gallery space itself, and the particular comportments that are presupposed here. Garden insists on deferring our gaze through one frame and then another, refusing the binary logic of our spectatorship in the development of subjecthood. The garden that we see, and the way we come to see it, follows a more wayward path. In O’Malley’s work, we begin to question all interactions as mediating behaviours, including our own. Perhaps even the steps we take as we walk out of the room.

Matt Packer, 2013, Independent Curator / Associate Director of Treignac Projet, France

*************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

‘O’Malley takes on Mayo: five galleries, one vision’, The Irish Times, Aug 30th, 2013, Aidan Dunne

***********************************************************************************************************************

Niamh O'Malley: Project Arts Centre ‘Garden’ The Sunday Times, Culture Section, June 23rd 2013 by Cristin Leach

There are three elements to O’Malley’s show. Two screens propped against the walls contain eerie projections on black fabric, while a sheet of glass painted on both sides stands upright in the middle of the gallery. Patches of paint like scraps of charred paper occupy the centre of this pane while pale grey and white leaves curl in from the edge of the frame. The structure is both two and three dimensional depending on how you look at it. This question of perspective is addressed in her projections too.

On the screens, hands hold a mirror that reflects foliage blowing in the breeze. Only fingers are visible as the pane tilts to adjust the view, but a black-clad body stands behind. The reflection reveals the breeze block boundaries of a suburban outdoor space. We see sky, clouds and espaliered fruit trees. Passion flowers climb the wall.

This is art about containment and freedom, perception and view, wilderness and domestication. It is immaculately presented and quietly effective work.

************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

http://www.billionjournal.com/time/51c.html

JUNE_2013, Half Empty/ Half Full by James Merrigan

NIAMH O'MALLEY Garden 26 April - 22 June, Project Arts Centre, Dublin

Excuse the following preamble but these were the thoughts and criticisms I had in anticipation of Niamh O’Malley’s solo exhibition ‘Garden‘ at Project Arts Centre, Dublin.

The Dublin art scene has a tendency of late to get saturated with the same artists solo exhibiting at the same commercial and public art spaces with (in some cases) only six-month intervals between exhibits. Is this another latent side-effect of the economic crisis? No room for polarised opinion or taste in neither politics nor art: just flatline consensus? Can private and public art institutions only afford to lazily follow local trends? Perhaps better scouting is needed, not just a quick dash to the neighbouring art gallery or arts centre to help those decide their borrowed taste for the coming year. It cannot be the case that directors and curators are in collective agreement about what shows are necessary and what artists are deserved of their place in the spotlight at the exact same moment and place in time. It could have more to do with directors and curators being on trend (which every accomplished art professional should be!) than coincidence. There is one good excuse, however, as all art spaces, whether private or public, plan their visual art programme years in advance, and it is quite possible (rather than believable) that an artist under the local radar is coincidently selected to solo exhibit twice in one year at two different spaces in one city. Especially when you consider the small art scene and the visibility that an artist on a vertical trajectory gets in one fell swoop when plucked from the herd. If that is the case shouldn’t the onus be on the artist to really consider what it means for them to produce work in such quick succession in the one city? For the other artists in the community this causes no small amount of begrudgery: something we don’t need anymore of, thank you! More importantly, it leaves artists who are doing the rounds in such a fast-track manner open to criticism, as observers can compare, contrast and judge the artist’s work tied or untied from art market strings. The variation of this trend that usually produces the most intriguing results is when a gallery represented artist shows outside of their usual haunt, which can go one of two ways: the artist sticks to their guns and repeats what they do on their home turf, or they try something out of their norm, challenging themselves, their audience, and their gallerist. What invariably gets cut first is the supplementary wall drawings for those artists who work in video and sculpture, while ‘wall artists’ such as painters go Gung-Ho, conceptualising what was a strict formalism in their usual gallery stable. However, some artists are more suited to being directed, others curated, and the few exiled stragglers are best left to their own devices.

As mentioned, these observations came to the surface in excited anticipation of Niamh O’Malley’s solo exhibition ‘Garden’ at Project Arts Centre. Not because O‘Malley is one of those artists that hops, skips, and jumps from private-to-public venue—the exact opposite is the case. Even though I saw her work for the first time outside of Green on Red Gallery at Dublin Contemporary (2011), followed by eva International (2012), this was her first solo show at a significant public venue in the heart of Dublin since exhibiting at The Hugh Lane in 2007. As presumed, the walls of PAC gallery are left naked: no supplementary signature drawings by O‘Malley to set collectors’ beady eyes flickering. Furthermore, the gallery is not decorated from end-to-end: one aloof sculpture and two wall-propped art objects is all that furnishes the space.

O’Malley’s large bench with a seemingly freestanding pane of glass, entitled Window, is one of a line of glass and mirror works that the artist has made over the last few years. Usually quite reductive in form, and successfully so, this time around O‘Malley has gone ‘decorative’, with a filigree of painted leaves creeping around formalist splats of paint. Although I wish I could, I cannot help referring back to Duchamp and his Large Glass when standing before this work. Especially considering the French artist and O‘Malley’s shared factious relationship with painting.

As the large glass stands half-full/ half-empty and centre-stage in the space, it is evident that O‘Malley still has a soft spot for painting. However, this work is not successful as either stage-setting for the exhibition or standalone artwork. It is too self-consciously made: the painted leaves jitter across the pane of glass as if unsure of their place in the work. It actually reads like a memorial plaque for post-World War painting. All that is left is a conceptual muddle of flaky black and grey embers of paint, packaged with corporate-like precision.

However, leaning against perpendicularly opposing walls is O’Malley at her visual best to date. Two of a kind, improvised wooden ‘trellises’, immaculately frame projection screens positioned at different levels on each frame. Surprisingly looking and feeling more analog than digital, the dual black and white film projections are of a rectangular mirror—held by the artist presumably—being tilted up-and-down to reflect (we are told in the accompanying text by curator Tessa Giblin in the exhibition foldout) O‘Malley’s Dublin inner city garden. But the cropped image deletes anything that could be read as autobiographical: all the observer is given is the artist’s unsteady pivoting hands along with a band of real environment that frames the mirror. The black cloth of the projection screens is left teasingly exposed at the edge, leaving a velvety band with the same exquisite presentation that O‘Malley executed in her Dublin Contemporary digital work Quarry (2011). The wooden ‘trellis’ compresses the lot. As observers we are pulled in-and-out of the successive frames, while being pushed back-and-forth by the reflected garden.

My previous mention of the World War in reference to O’Malley’s freestanding Window, and combined with her Garden ‘frames’, I am reminded of what Gerhard Richter once said about the photograph being a ‘world’ unto itself, the memory of the photographer and the memory of the person photographed contained within the limits of each individual image, whilst everything outside the photographic frame of reference is forgotten, buried at the edges, but paradoxically alive. Expanding on Richter’s metaphysical observation we could diagnose the German artist’s painted simulations of his family photographs—his own family were literally ‘lost’ to him when the artist, alone, left his home of East Germany before the Berlin Wall came into existence—as a way of extracting something that is exterior to the photographic frame of reference. Richter’s personal history takes on further signification with regard to perimeters, borders, framing, when the artist revealed that he never saw his family again, the Berlin Wall enclosing them in a real an unmovable frame. The ‘reality’ that Richter paints is personally invested with family, friends, German history. And so, if Richter’s desire is to use painting to rediscover an essence of memory through mood and sensation, essences that lie beyond the dead photographic frame of reference, the question is: what desires are being played beyond O’Malley’s ‘frame’, if anything?

We could talk of gardens and colonialism and other such academic detours, but what makes this work by O‘Malley special is its self-reflexive existence inside the frame. The autobiographical reference to O’Malley’s garden in the accompanying essay is superfluous. This could be any garden, or for that matter a piece of manicured urban landscape beside passing traffic. Whatever existing sloppy everyday that exists outside the frame is deleted by the up-close crop of reality: when O’Malley does ’sloppy’ it is precisely scaffolded. And although there could be criticism flung at the compressed curation of the exhibition, whereby the observer has to crop all the uninhabited space that surrounds the three art objects, the fact is O’Malley’s raison d'être seems to be to make visually compressed art objects. The artist‘s decision to make two art objects that mirror each other in form and content is key to the dual artwork’s success. One on its own would have been an elegant objet d’art and nothing more. Instead, O‘Malley presents a very sexy simulacrum of reality whilst also stripping bare (like Duchamp’s Bride) the vanity of the artwork—a vanity that is certainly not visually empty.

************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Niamh O’Malley; on looking and materiality

Project Arts Centre, Dublin June 2013, online review by Andrea Kirsh

On entering the gallery at Project Arts Centre,where Niamh O’Malley‘s Garden is on view through June 22, the most striking first impression is that all the color has been drained. It is a resolutely black and white world. In the midst of the space a large pane of glass, framed as a window, stands in a slot in the middle of a two-sided bench. The glass has seemingly-random patches of paint, as if the artist was testing her brushes, as well as small areas that appear to be shadows of vines. The double-sided glass raises the question of whether the viewer is looking into or out of the window. This focus on the multiple spacial and visual qualities of a window is the same territory that Monet explored in his late paintings of the pond in his garden, where the water’s surface functioned simultaneously as a plane on which lilies floated, as a window, through which to see the water below, and as a mirror that reflected the surrounding trees and sky.